种植体周围疾病的早期诊断和非手术性治疗——叙述性文献综述

前言

种植体周围疾病是种植体治疗中可导致种植体失败常见的生物学并发症[1]。临床医师应了解这些常见疾病的病因和致病因素。可以及时对有风险的种植体进行早期识别、诊断和最初的非手术治疗。这篇叙述性综述旨在帮助临床医师了解种植体周围疾病的主要病因、常见的致病因素、早期诊断科学和非手术治疗方式。

种植体周黏膜炎是一种局限于种植体周围附着软组织的炎症[2]。患有种植体周黏膜炎的种植体常伴有种植体周边缘黏膜红斑和水肿,此外还有轻微探诊出血[2]。与菌斑引起的牙龈炎类似,种植体周黏膜炎在正确治疗下是可逆的[3]。相比之下,种植周炎是指发生在牙槽骨和附着软组织的炎症,导致牙槽骨不可逆的破坏[3]。与牙周炎相似,种植体周炎患者的龈沟液中的促炎细胞因子如白介素1β(IL-1β)和基质金属蛋白酶8(MMP8)的水平也高于健康组[4]。除了种植体周黏膜炎的临床症状外,患有种植体周黏膜炎的种植体可能还伴随化脓、疼痛和松动症状。根据最近的一项荟萃分析[3],种植体周黏膜炎的患病率约为43%而种植体周炎的患病率为22%。同样,另一项荟萃分析报告了种植体周黏膜炎和种植体周炎的患病率分别为30.7%和9.6%[5]。观察到的患病率差异可能源于对疾病的不同定义和研究人群差异。种植体周围疾病影响到大量的种植体和患者[6]。此外,种植体周围疾病,特别是种植体周炎的进展是一种非线性的加速模式,因此其早期诊断至关重要[7]。在大多数情况下,种植体周围疾病是无症状的,患者无法察觉,使得诊断具有挑战性[8]。因此,临床医师应定期持续监测种植体的功能。为避免种植体脱落,被诊断为种植体周围疾病的患者应立即接受治疗[9]。因此,临床医师应该了解种植体周围疾病的病理生理学,包括诊断、病因和影响因素[6]。了解这种新出现的疾病是成功设计预防方案,识别疾病的早期征兆并及时提供保守的非手术治疗的关键[1,6]。我们根据叙述性评论报告清单撰写以下文章(https://fomm.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/fomm-21-58/rc)[10]。

方法

用以下关键词检索PubMed数据库:“种植体周炎/分类”[Mesh]或“种植体周炎/并发症”[Mesh]或“种植体周炎/诊断”[Mesh]或种植体周炎/流行病学”[Mesh]或”种植周炎/病理学“[MESH]或”种植周炎/生理病理学“[MESH]或”种植周炎/手术“[MESH]或”种植周炎/治疗“[MESH]或”种植体周黏膜炎“。纳入标准为发表于1993年1月1日至2021年4月30日的英文文献,涉及种植体周围疾病(种植体周黏膜炎、种植体周炎)、流行病学、病因学、危险因素、诊断及非手术治疗。排除任何不符合纳入标准的研究。2位评审员(TK,HHY)根据他们在该主题的专业知识,通过审查标题、摘要和全文进一步筛选文章。在达成共识之前,2位评审员在选择文章方面的任何分歧都由第3位评审员(LL)解决。通过手动搜索本叙述性综述中所包括的文章的参考列表,进一步扩大了搜索范围。

种植体周围疾病的病因和致病因素

牙菌斑

牙菌斑是种植体周围疾病最主要的病因[3]。种植体上牙菌斑的聚集触发炎症反应导致种植体周黏膜炎和种植体周围炎[11]。显而易见,从病因和发病机制来看,牙周病和种植体周围疾病没有功能区别[12]。早期种植体周围期疾病可能与微生物群改变有关,类似于牙周炎[13]。在牙周炎和种植体周炎中,对微生物的炎症反应最终可能导致牙或种植体周围牙槽骨的进行性破坏[7,12,14]。研究证据表明,在没有临床软组织炎症的情况下,种植体周围进行性牙槽嵴顶骨丧失极其罕见[7]。考虑到种植体周围黏膜下组织中牙菌斑可能引发种植体周围疾病[1,12],种植体周围疾病的预防性和积极性治疗都应以持续清除牙菌斑为目标。口腔卫生差的患者患种植体周围炎的风险是口腔卫生佳患者的15倍[15]。根据已成功应用于牙周炎治疗[16,17]的相关原因疗法的原则,临床医师应教育可能的种植患者关于种植周围疾病的发病机制以及致病因素——牙菌斑。此外,临床医师应在进行实际的牙科种植治疗之前帮助患者进行有效的家庭口腔护理,即使是计划进行全口拔牙和种植治疗的患者[18]。只有在患者了解种植体周围疾病以及家庭口腔护理在预防种植体周围疾病方面起到治疗作用之后,才应该开始种植治疗[1,18]。在修复阶段,临床医师应认真设计义齿。义齿不应促进斑块堆积,而应允许患者毫无困难地进行家庭护理治疗。在完成种植体的修复治疗后,临床医师还应根据但不限于修复体类型、楔状隙大小和患者的手动灵活性,向每个患者推荐一套特定的菌斑去除仪器[19]。

吸烟

吸烟患者接受种植体治疗后患种植体周围疾病的风险更高[3,20-22]。Levin等开展的研究[2011][21]入组2,336枚种植体,随访时间144个月,结果显示吸烟者与不吸烟者在前50个月的种植体存活率相似。然而,50个月后,吸烟者种植失败的风险表现为不吸烟者的2.76倍[21]。此外,在最近对710个种植体的队列研究中,吸烟者(现在或以前)种植失败的几率是不吸烟者[23]的6.35倍。与牙周炎相似,吸烟者与不吸烟者相比,种植体周炎的风险较高,可能由于他们潜在携带牙周病原体和宿主免疫反应的改变[24-27]。在开始种植治疗之前,临床医师应将重点放在患者戒烟上,确保种植治疗的长期成功。此外,临床医师应清楚地告知吸烟患者种植失败风险,并长期持续监测种植体,特别是超过50个月的功能[21]。

患牙周炎或有牙周炎病史且缺乏定期维持治疗

患牙周炎或有牙周炎病史的患者患种植体周围疾病的风险更高[7,15,28]。根据最近一项荟萃分析系统回顾,患牙周炎和有牙周炎病史的患者种植周炎风险是牙周健康个体的2.15倍[29]。在一项严重牙周炎患者种植治疗的长期队列研究中,与牙周健康的患者相比,牙周炎患者患种植周炎的风险高达14倍[30]。在最近的一项10年随访的回顾性研究中,83.3%的种植失败发生在复发性牙周病患者,而16.7%的种植失败发生在无复发牙周病的患者[31]。此外,有6 mm或以上残留牙周袋的患者发生种植体周围炎的风险比没有残留牙周袋的患者高5.47倍[32]。据报道,常见的牙周病原体从邻近有牙周袋的自然牙列传播到种植体周围,这反过来可能导致局部宿主促炎反应的启动,从而导致易感患者种植体周围疾病[33]。最近的一项横断面研究报告了从牙周炎部位收集的牙周龈沟液和从种植体周围部位收集的种植体周围牙周龈沟液之间类似的促炎细胞因子谱[34]。

定期的种植体维护治疗也与降低种植体周围疾病发生率有关[35,36]。在一项为期5年的随访研究中调查了患者种植体周黏膜炎的发生率,未预防性维护治疗组为43.9%,定期预防性维护治疗组为18.0%[35]。在一项荟萃分析系统回顾中,在1~10年的随访期内,接受定期种植体周围维护治疗的患者比没有接受维护治疗的患者的种植体存活率增加了10%[37]。此外,接受常规维护治疗的患者在4年至68.2个月的随访期[37]中,种植体周黏膜炎和种植体周炎的患病率分别降低了43%和75%。定期维护治疗包括口腔卫生加强和专业机械性菌斑去除[37]。在维护治疗期间,临床医师应进行全面的牙周和种植体周黏膜检查。临床医师应该理解并与患者讨论,种植治疗不能仅局限于种植体的放置和修复,还应实施种植体周围的维护治疗以防止生物并发症,来确保种植体的长期存活[38]。

修复性考虑

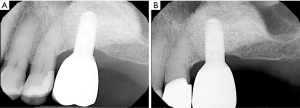

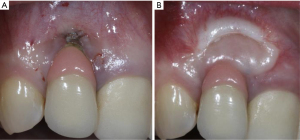

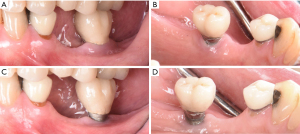

由于牙菌斑是种植体周围疾病的一个致病因素,因此种植牙的修复体应该仔细设计或修改,以便患者能够轻松有效地去除牙菌斑[3]。在最近的一项横断面研究中,研究者评估了171个种植体,只有46%义齿能够去除邻接的牙菌斑[39]。临床医师应该基于邻间隙、患者的手动灵活性和积极程度(图1)[19]教育和帮助患者培养有效使用特殊口腔仪器的能力。如果可能,螺丝固位修复体比粘接固位修复体效果要更好,因为可以避免过多的粘接剂进入种植体周龈沟内[40-43]。种植体周龈沟粘接剂残留量过多与种植体周围炎风险增加相关[40-42,44]。如果使用粘接固位修复体,临床医师应考虑将基牙修复体边缘尽可能冠向放置,以便在放置过程中更有效地去除多余粘接剂(图2)[45,46]。牙种植体修复的咬合方案应精心设计,避免因正中或偏侧运动而过咬合。尽管文献有限,但在动物研究中咬合对牙种植体的负面影响被提到[47-53]。与天然牙列相似[54],种植修复体周围的开放邻接也与更高的探诊深度、菌斑指数和牙龈指数相关,并且患种植体周围疾病的风险高达1.57倍[55]。在植入前,应仔细评估基牙和修复体是否表面质地粗糙,这些粗糙纹理可能是实验室制造过程中形成的。粗糙基牙表面可能比标准抛光表面牙菌斑含量多25倍,这会促进牙菌斑的局部积累,可能导致种植体周围疾病的发生[56]。

糖尿病

未控制糖尿病的患者发生种植体周围疾病风险更高[7,22,57,58]。在最近的一项荟萃分析中,糖尿病患者发生种植体周围炎的风险是非糖尿病患者的1.46倍[57]。具体而言,高血糖患者发生种植体周围炎的风险是正常血糖患者的3.39倍[57]。与血糖正常的患者相比,可能是由于宿主免疫反应、结缔组织代谢以及种植体周围的微血管发生了变化[59-64],高血糖患者发生种植体周围炎的风险增加。因此在开始种植治疗之前,临床医师应该告知糖尿病患者发生种植周炎的风险增加。如有必要,应考虑咨询相关医师。

缺乏角化组织

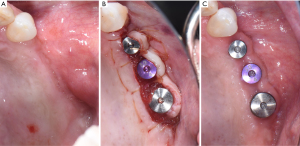

类似于天然牙列,缺乏角化组织的种植体周围黏膜炎症反应明显多于有足够角化组织的种植体周围黏膜[65,66]。足够数量的角化组织可能会减少种植体周围的牙菌斑堆积,并减少种植体周围的黏膜萎缩(图3)[67]。此外,种植体角化黏膜宽度小于2 mm的种植体发生种植体周黏膜炎和种植体周周炎的风险分别是1.53和1.87倍[68]。最近的一项研究比较了增加软组织种植体和未增加软组织种植体,报告了软组织增加与探诊出血减少和探诊深度显著相关。类似地,与薄型生物型种植体[69]相比,厚软组织生物型种植体的探诊出血、黏膜退缩、边缘骨丧失和临床附着水平显著降低。

如果预期的种植体部位缺乏角化组织,临床医师应考虑增加软组织来控制牙菌斑并减少种植体周围的炎症,这可能会将种植体周围疾病的发生率降至最低(图4)。在种植体植入和第二阶段手术时规划翻瓣是非常重要的,可能避免未来软组织处理的需要。

早期诊断

早期诊断使临床医师能够及时提供必要的处理。因此,临床医师应该在常规维护治疗期间持续监测种植体[1]。具有上述危险因素和促进因素的患者应仔细监测种植体周围疾病的任何早期征兆。风险因素和致病因素也应改变或消除来减少疾病发生和发展的可能性[6]。完成牙种植体修复后不久应获取基线临床和放射学参数,以便与维护治疗的参数进行常规比较。部分文献将特定范围的探诊深度与种植体周围健康联系起来[2,70]。种植体中的探诊深度随软组织厚度的不同而变化,在种植体周围疾病的诊断中提供的价值有限[2,70]。

因此,临床医师应该更多地关注探诊深度的任何变化(与基线相比)。探诊深度的增加可能与种植体周黏膜水肿和探诊阻力降低有关,这可能提示种植体周炎症或疾病的存在[2,7,71]。探诊出血也应被认为有助于区分种植体周围健康和疾病[2,7,71]。根据最近的一项系统回顾和荟萃分析,对于在探诊时出血的种植体,有24%的概率被诊断为种植体周围炎[72]。此外,在最近对334个患有种植体周炎的种植体的分析中,大约28%的种植体在探诊时表现为化脓,主要是在颊侧[73]。定期拍X线片来评估牙槽骨丧失的现状或进展。推荐采用长锥体平行投照技术评估牙槽嵴顶水平[74]。一般来说,第一年边缘骨丢失1 mm,此后每年平均丢失0.2 mm被认为是可以接受的[75]。因此,任何超过这一可接受变化的骨丢失都可能需要进一步评估潜在的种植体周围疾病。如有必要,可利用锥形束计算机体层摄影术对牙种植体周围的牙槽骨进行颊舌面可视化[76]。在最近一项对接受种植体治疗的患者的评估中,在识别种植体周围炎方面,探诊出血、探查化脓以及放射学上骨丧失大于0.5~1 mm提供了高诊断准确率[77]。其他参数,如黏膜退缩、残留角化组织的宽度、任何炎症迹象(即红斑、水肿)和移动度也应记录下来[2,7]。可记录菌斑指数来持续评估患者对建议的家庭口腔护理的依从性[78]。

种植体周非手术治疗

种植体周围疾病的初步治疗包括局部非手术机械性菌斑去除结合家庭护理治疗。应用病因相关治疗理念,针对病因——种植体周围的牙菌斑[16,17]。临床医师应该教育患者牙菌斑是主要致病因素,并指导他们在家中有效地去除牙菌斑[16-18]。临床医师应该仔细审查和更新患者的医疗病史和牙科病史来发现任何潜在的风险指标,如吸烟习惯和糖尿病情况。临床医师应进一步评估患者是否有任何复发或活动性牙周病。应仔细检查种植体是否存在过量粘接剂残留物,过度正中和侧向偏位咬合接触,以及开放邻接。如有必要,应对现有修复体进行修改或更改以便控制菌斑。在最近的一项随机对照试验中,根据出血指数和探诊深度的变化来衡量,通过修改义齿外形来改善家庭护理治疗,显著改善了种植周黏膜炎的标准机械治疗的临床结果[79]。在消除和纠正上述因素后,应开始非手术机械性菌斑去除。对于种植体周黏膜炎,炎症局限在软组织中,种植体周围没有明显的牙槽骨丢失,传统的非手术机械疗法结合家庭护理疗法是标准治疗方法,可减少0.5~1 mm的牙周袋深度,减少15%~40%探诊出血[74,80-83]。对于种植体周围有牙槽骨丢失的种植体周围炎,临床医师应假定种植体表面受到严重污染,并应使用传统的自动和手动刮治器,以确保有效地去除受污染的种植体周围的牙菌斑或生物膜(图5)[84]。单独的非手术机械清创通常可以减少20%~50%探诊出血,在某些情况下,种植体周围炎[74,85-89]牙周袋变浅(≤1 mm)。因此,在晚期病例中,疾病不太可能完全消失,许多病例需要辅助治疗以提高改善的程度[74]。对于容易接近的表面,可以使用高速硬质合金钻头和严格的水冷却进行种植成形术,以进一步去除残留的牙菌斑及其相关碎片,并将粗糙的表面转化为光滑的表面,使患者和治疗临床医师在维护阶段能够更有效地去除牙菌斑[56,90,91]。除非手术治疗外,多种辅助治疗方法也被报道,包括全身抗生素、局部给药、激光、光动力疗法和空气抛光。然而,考虑到文献中证据有限,临床医师应该谨慎地使用这些方法[74,85,87,88,92-94]。

种植体周再评估和维护治疗

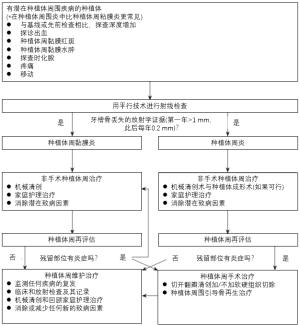

在完成非手术的种植体周治疗后,应在4~6周内进行种植体周再评估来确定改善的程度。对于无反应部位,特别是晚期种植体周围炎,可能需要手术干预以进一步根除遗留疾病[95]。手术措施包括但不限于传统的切开翻瓣清创加或不加切除手术、同期种植体周引导骨再生治疗或两者的组合[96-98]。在种植体周围疾病得到成功解决,甚至种植体治疗初步完成(即种植体修复)后,患者应定期接受种植体维护治疗。维护间隔应至少每隔5~6个月进行一次;但应根据每位患者患种植体周围疾病的风险[36,38,99]不断更新或修改。在维护治疗期间,临床医师应持续监测患者的病情复发或发病情况。如前所述,定期的种植体维护治疗可显著降低患种植体周围疾病的风险[35-37]。图6显示了种植体周围疾病处理的各个阶段的简化流程图。

结论

种植体周围疾病是种植体治疗中常见的生物学并发症。在种植体治疗的所有阶段(即治疗计划、手术、修复和维护阶段),临床医师和患者应不断针对其病因、牙菌斑和其他促成因素,将发生种植体周围疾病的风险降至最低。此外,在维护治疗期间,应该仔细检查种植体是否有任何早期征兆提示种植体周围疾病的发生。如有需要应及时开始非手术治疗,然后对效果不佳部位进行手术治疗。

Acknowledgments

Funding: None.

Footnote

Provenance and Peer Review: This article was commissioned by the Guest Editor (Ole T. Jensen) for the series “Current Advances in Treatment of Peri-Implantitis” in Frontiers of Oral and Maxillofacial Medicine. The article has undergone external peer review.

Reporting Checklist: The authors have completed the Narrative Review reporting checklist. Available at https://fomm.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/fomm-21-58/rc

Conflicts of Interest: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form (available at https://fomm.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/fomm-21-58/coif). The series “Current Advances in Treatment of Peri-Implantitis” was commissioned by the editorial office without any funding or sponsorship. The authors have no other conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Statement: The authors are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Open Access Statement: This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which permits the non-commercial replication and distribution of the article with the strict proviso that no changes or edits are made and the original work is properly cited (including links to both the formal publication through the relevant DOI and the license). See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

References

- Kwon T, Wang CW, Salem DM, et al. Nonsurgical and surgical management of biologic complications around dental implants: peri-implant mucositis and peri-implantitis. Quintessence Int 2020;51:810-20. [PubMed]

- Berglundh T, Armitage G, Araujo MG, et al. Peri-implant diseases and conditions: Consensus report of workgroup 4 of the 2017 World Workshop on the Classification of Periodontal and Peri-Implant Diseases and Conditions. J Periodontol 2018;89:S313-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Jepsen S, Berglundh T, Genco R, et al. Primary prevention of peri-implantitis: managing peri-implant mucositis. J Clin Periodontol 2015;42:S152-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hentenaar DFM, De Waal YCM, Vissink A, et al. Biomarker levels in peri-implant crevicular fluid of healthy implants, untreated and non-surgically treated implants with peri-implantitis. J Clin Periodontol 2021;48:590-601. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Atieh MA, Alsabeeha NH, Faggion CM Jr, et al. The frequency of peri-implant diseases: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Periodontol 2013;84:1586-98. [PubMed]

- Lee CT, Huang YW, Zhu L, et al. Prevalences of peri-implantitis and peri-implant mucositis: systematic review and meta-analysis. J Dent 2017;62:1-12. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Schwarz F, Derks J, Monje A, et al. Peri-implantitis. J Periodontol 2018;89:S267-90. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Romandini M, Pedrinaci I, Lima C, et al. Prevalence and risk/protective indicators of buccal soft tissue dehiscence around dental implants. J Clin Periodontol 2021;48:455-63. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Salvi GE, Cosgarea R, Sculean A. Prevalence and Mechanisms of Peri-implant Diseases. J Dent Res 2017;96:31-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Green BN, Johnson CD, Adams A. Writing narrative literature reviews for peer-reviewed journals: secrets of the trade. J Chiropr Med 2006;5:101-17. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Renvert S, Quirynen M. Risk indicators for peri-implantitis. A narrative review. Clin Oral Implants Res 2015;26:15-44. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Heitz-Mayfield LJ, Lang NP. Comparative biology of chronic and aggressive periodontitis vs. peri-implantitis. Periodontol 2000 2010;53:167-81. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lu H, Yan X, Zhu B, et al. The occurrence of peri-implant mucositis associated with the shift of submucosal microbiome in patients with a history of periodontitis during the first two years. J Clin Periodontol 2021;48:441-54. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Page RC, Offenbacher S, Schroeder HE, et al. Advances in the pathogenesis of periodontitis: summary of developments, clinical implications and future directions. Periodontol 2000 1997;14:216-48. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ferreira SD, Silva GLM, Cortelli JR, et al. Prevalence and risk variables for peri-implant disease in Brazilian subjects. J Clin Periodontol 2006;33:929-35. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kwon T, Levin L. Cause-related therapy: a review and suggested guidelines. Quintessence Int 2014;45:585-91. [PubMed]

- Kwon T, Salem DM, Levin L. Nonsurgical periodontal therapy based on the principles of cause-related therapy: rationale and case series. Quintessence Int 2019;50:370-6. [PubMed]

- Kwon T, Wang JCW, Levin L. Home Care is Therapeutic. Should We Use the Term "Home-care Therapy" Instead of "Instructions"? Oral Health Prev Dent 2020;18:397-8. [PubMed]

- Liang P, Ye S, McComas M, et al. Evidence-based strategies for interdental cleaning: a practical decision tree and review of the literature. Quintessence Int 2021;52:84-95. [PubMed]

- Carral C, Flores-Guillén J, Figuero E, et al. Peri-implant radiographic bone level and associated factors in Spain. J Clin Periodontol 2021;48:805-15. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Levin L, Ofec R, Grossmann Y, et al. Periodontal disease as a risk for dental implant failure over time: a long-term historical cohort study. J Clin Periodontol 2011;38:732-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Dreyer H, Grischke J, Tiede C, et al. Epidemiology and risk factors of peri-implantitis: A systematic review. J Periodontal Res 2018;53:657-81. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Takamoli J, Pascual A, Martinez-Amargant J, et al. Implant failure and associated risk indicators: A retrospective study. Clin Oral Implants Res 2021;32:619-28. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Camelo-Castillo AJ, Mira A, Pico A, et al. Subgingival microbiota in health compared to periodontitis and the influence of smoking. Front Microbiol 2015;6:119. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Haffajee AD, Socransky SS. Relationship of cigarette smoking to the subgingival microbiota. J Clin Periodontol 2001;28:377-88. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Persson L, Bergström J, Ito H, et al. Tobacco smoking and neutrophil activity in patients with periodontal disease. J Periodontol 2001;72:90-5. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Shivanaikar SS, Faizuddin M, Bhat K. Effect of smoking on neutrophil apoptosis in chronic periodontitis: an immunohistochemical study. Indian J Dent Res 2013;24:147. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Renvert S, Aghazadeh A, Hallström H, et al. Factors related to peri-implantitis - a retrospective study. Clin Oral Implants Res 2014;25:522-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ferreira SD, Martins CC, Amaral SA, et al. Periodontitis as a risk factor for peri-implantitis: Systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. J Dent 2018;79:1-10. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Swierkot K, Lottholz P, Flores-de-Jacoby L, et al. Mucositis, peri-implantitis, implant success, and survival of implants in patients with treated generalized aggressive periodontitis: 3- to 16-year results of a prospective long-term cohort study. J Periodontol 2012;83:1213-25. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Guarnieri R, Di Nardo D, Di Giorgio G, et al. Longevity of Teeth and Dental Implants in Patients Treated for Chronic Periodontitis Following Periodontal Maintenance Therapy in a Private Specialist Practice: A Retrospective Study with a 10-Year Follow-up. Int J Periodontics Restorative Dent 2021;41:89-98. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Cho-Yan Lee J, Mattheos N, Nixon KC, et al. Residual periodontal pockets are a risk indicator for peri-implantitis in patients treated for periodontitis. Clin Oral Implants Res 2012;23:325-33. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Aoki M, Takanashi K, Matsukubo T, et al. Transmission of periodontopathic bacteria from natural teeth to implants. Clin Implant Dent Relat Res 2012;14:406-11. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Jansson L, Lundmark A, Modin C, et al. Intra-individual cytokine profile in peri-implantitis and periodontitis: A cross-sectional study. Clin Oral Implants Res 2021;32:559-68. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Costa FO, Takenaka-Martinez S, Cota LO, et al. Peri-implant disease in subjects with and without preventive maintenance: a 5-year follow-up. J Clin Periodontol 2012;39:173-81. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Monje A, Wang HL, Nart J. Association of Preventive Maintenance Therapy Compliance and Peri-Implant Diseases: A Cross-Sectional Study. J Periodontol 2017;88:1030-41. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lin CY, Chen Z, Pan WL, et al. The effect of supportive care in preventing peri-implant diseases and implant loss: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Oral Implants Res 2019;30:714-24. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Monje A, Aranda L, Diaz KT, et al. Impact of Maintenance Therapy for the Prevention of Peri-implant Diseases: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. J Dent Res 2016;95:372-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Pons R, Nart J, Valles C, et al. Self-administered proximal implant-supported hygiene measures and the association to peri-implant conditions. J Periodontol 2021;92:389-99. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Korsch M, Walther W. Peri-Implantitis Associated with Type of Cement: A Retrospective Analysis of Different Types of Cement and Their Clinical Correlation to the Peri-Implant Tissue. Clin Implant Dent Relat Res 2015;17:e434-43. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kotsakis GA, Zhang L, Gaillard P, et al. Investigation of the Association Between Cement Retention and Prevalent Peri-Implant Diseases: A Cross-Sectional Study. J Periodontol 2016;87:212-20. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Quaranta A, Lim ZW, Tang J, et al. The Impact of Residual Subgingival Cement on Biological Complications Around Dental Implants: A Systematic Review. Implant Dent 2017;26:465-74. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Staubli N, Walter C, Schmidt JC, et al. Excess cement and the risk of peri-implant disease - a systematic review. Clin Oral Implants Res 2017;28:1278-90. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Wilson TG Jr, Valderrama P, Burbano M, et al. Foreign bodies associated with peri-implantitis human biopsies. J Periodontol 2015;86:9-15. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Linkevicius T, Vindasiute E, Puisys A, et al. The influence of the cementation margin position on the amount of undetected cement. A prospective clinical study. Clin Oral Implants Res 2013;24:71-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Linkevicius T, Puisys A, Vindasiute E, et al. Does residual cement around implant-supported restorations cause peri-implant disease? A retrospective case analysis. Clin Oral Implants Res 2013;24:1179-84. [PubMed]

- Chambrone L, Chambrone LA, Lima LA. Effects of occlusal overload on peri-implant tissue health: a systematic review of animal-model studies. J Periodontol 2010;81:1367-78. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Chang M, Chronopoulos V, Mattheos N. Impact of excessive occlusal load on successfully-osseointegrated dental implants: a literature review. J Investig Clin Dent 2013;4:142-50. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Isidor F. Histological evaluation of peri-implant bone at implants subjected to occlusal overload or plaque accumulation. Clin Oral Implants Res 1997;8:1-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kim Y, Oh TJ, Misch CE, et al. Occlusal considerations in implant therapy: clinical guidelines with biomechanical rationale. Clin Oral Implants Res 2005;16:26-35. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Merin RL. Repair of peri-implant bone loss after occlusal adjustment: a case report. J Am Dent Assoc 2014;145:1058-62. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Naert I, Duyck J, Vandamme K. Occlusal overload and bone/implant loss. Clin Oral Implants Res 2012;23:95-107. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Passanezi E, Sant'Ana AC, Damante CA. Occlusal trauma and mucositis or peri-implantitis? J Am Dent Assoc 2017;148:106-12. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Koral SM, Howell TH, Jeffcoat MK. Alveolar bone loss due to open interproximal contacts in periodontal disease. J Periodontol 1981;52:447-50. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Latimer JM, Gharpure AS, Kahng HJ, et al. Interproximal open contacts between implant restorations and adjacent natural teeth as a risk-indicator for peri-implant disease-A cross-sectional study. Clin Oral Implants Res 2021;32:598-607. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Quirynen M, van der Mei HC, Bollen CM, et al. An in vivo study of the influence of the surface roughness of implants on the microbiology of supra- and subgingival plaque. J Dent Res 1993;72:1304-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Monje A, Catena A, Borgnakke WS. Association between diabetes mellitus/hyperglycaemia and peri-implant diseases: Systematic review and meta-analysis. J Clin Periodontol 2017;44:636-48. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- French D, Ofec R, Levin L. Long term clinical performance of 10 871 dental implants with up to 22 years of follow-up: A cohort study in 4247 patients. Clin Implant Dent Relat Res 2021;23:289-97. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Mealey BL, Oates TWAmerican Academy of Periodontology. Diabetes mellitus and periodontal diseases. J Periodontol 2006;77:1289-303. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lamster IB, Pagan M. Periodontal disease and the metabolic syndrome. Int Dent J 2017;67:67-77. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lamster IB, Cheng B, Burkett S, et al. Periodontal findings in individuals with newly identified pre-diabetes or diabetes mellitus. J Clin Periodontol 2014;41:1055-60. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lalla E, Lamster IB, Stern DM, et al. Receptor for advanced glycation end products, inflammation, and accelerated periodontal disease in diabetes: mechanisms and insights into therapeutic modalities. Ann Periodontol 2001;6:113-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lalla E, Lamster IB, Drury S, et al. Hyperglycemia, glycoxidation and receptor for advanced glycation endproducts: potential mechanisms underlying diabetic complications, including diabetes-associated periodontitis. Periodontol 2000 2000;23:50-62. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Schmidt AM, Weidman E, Lalla E, et al. Advanced glycation endproducts (AGEs) induce oxidant stress in the gingiva: a potential mechanism underlying accelerated periodontal disease associated with diabetes. J Periodontal Res 1996;31:508-15. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Monje A, Blasi G. Significance of keratinized mucosa/gingiva on peri-implant and adjacent periodontal conditions in erratic maintenance compliers. J Periodontol 2019;90:445-53. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Schrott AR, Jimenez M, Hwang JW, et al. Five-year evaluation of the influence of keratinized mucosa on peri-implant soft-tissue health and stability around implants supporting full-arch mandibular fixed prostheses. Clin Oral Implants Res 2009;20:1170-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Chackartchi T, Romanos GE, Sculean A. Soft tissue-related complications and management around dental implants. Periodontol 2000 2019;81:124-38. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Gharpure AS, Latimer JM, Aljofi FE, et al. Role of thin gingival phenotype and inadequate keratinized mucosa width (<2 mm) as risk indicators for peri-implantitis and peri-implant mucositis. J Periodontol 2021; Epub ahead of print. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Isler SC, Uraz A, Kaymaz O, et al. An Evaluation of the Relationship Between Peri-implant Soft Tissue Biotype and the Severity of Peri-implantitis: A Cross-Sectional Study. Int J Oral Maxillofac Implants 2019;34:187-196. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Coli P, Sennerby L. Is Peri-Implant Probing Causing Over-Diagnosis and Over-Treatment of Dental Implants? J Clin Med 2019;8:1123. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Renvert S, Persson GR, Pirih FQ, et al. Peri-implant health, peri-implant mucositis, and peri-implantitis: Case definitions and diagnostic considerations. J Periodontol 2018;89:S304-12. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hashim D, Cionca N, Combescure C, et al. The diagnosis of peri-implantitis: A systematic review on the predictive value of bleeding on probing. Clin Oral Implants Res 2018;29:276-93. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Monje A, Vera M, Muñoz-Sanz A, et al. Suppuration as diagnostic criterium of peri-implantitis. J Periodontol 2021;92:216-24. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Renvert S, Hirooka H, Polyzois I, et al. Diagnosis and non-surgical treatment of peri-implant diseases and maintenance care of patients with dental implants - Consensus report of working group 3. Int Dent J 2019;69:12-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Albrektsson T, Zarb G, Worthington P, et al. The long-term efficacy of currently used dental implants: a review and proposed criteria of success. Int J Oral Maxillofac Implants 1986;1:11-25. [PubMed]

- Dave M, Davies J, Wilson R, et al. A comparison of cone beam computed tomography and conventional periapical radiography at detecting peri-implant bone defects. Clin Oral Implants Res 2013;24:671-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Romandini M, Berglundh J, Derks J, et al. Diagnosis of peri-implantitis in the absence of baseline data: A diagnostic accuracy study. Clin Oral Implants Res 2021;32:297-313. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- O'Leary TJ, Drake RB, Naylor JE. The plaque control record. J Periodontol 1972;43:38. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- de Tapia B, Mozas C, Valles C, et al. Adjunctive effect of modifying the implant-supported prosthesis in the treatment of peri-implant mucositis. J Clin Periodontol 2019;46:1050-60. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Aimetti M, Mariani GM, Ferrarotti F, et al. Adjunctive efficacy of diode laser in the treatment of peri-implant mucositis with mechanical therapy: A randomized clinical trial. Clin Oral Implants Res 2019;30:429-38. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Serino G, Wada M. Non-surgical mechanical treatment of peri-implant mucositis: the effect of sub-mucosal mechanical instrumentation following supra-mucosal plaque removal. A 7-month prospective single cohort study. Eur J Oral Implantol 2018;11:455-66. [PubMed]

- Riben-Grundstrom C, Norderyd O, André U, et al. Treatment of peri-implant mucositis using a glycine powder air-polishing or ultrasonic device: a randomized clinical trial. J Clin Periodontol 2015;42:462-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Gomes SC, Corvello P, Romagna R, et al. How do peri-implant mucositis and gingivitis respond to supragingival biofilm control - an intra-individual longitudinal cohort study. Eur J Oral Implantol 2015;8:65-73. [PubMed]

- Fox SC, Moriarty JD, Kusy RP. The effects of scaling a titanium implant surface with metal and plastic instruments: an in vitro study. J Periodontol 1990;61:485-90. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hentenaar DFM, De Waal YCM, Stewart RE, et al. Erythritol airpolishing in the non-surgical treatment of peri-implantitis: A randomized controlled trial. Clin Oral Implants Res 2021;32:840-52. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Wagner TP, Pires PR, Rios FS, et al. Surgical and non-surgical debridement for the treatment of peri-implantitis: a two-center 12-month randomized trial. Clin Oral Investig 2021; Epub ahead of print. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Machtei EE, Romanos G, Kang P, et al. Repeated delivery of chlorhexidine chips for the treatment of peri-implantitis: A multicenter, randomized, comparative clinical trial. J Periodontol 2021;92:11-20. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Machtei EE, Frankenthal S, Levi G, et al. Treatment of peri-implantitis using multiple applications of chlorhexidine chips: a double-blind, randomized multi-centre clinical trial. J Clin Periodontol 2012;39:1198-205. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Arısan V, Karabuda ZC, Arıcı SV, et al. A randomized clinical trial of an adjunct diode laser application for the nonsurgical treatment of peri-implantitis. Photomed Laser Surg 2015;33:547-54. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Sivolella S, Brunello G, Michelon F, et al. Implantoplasty: Carbide burs vs diamond sonic tips. An in vitro study. Clin Oral Implants Res 2021;32:324-36. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- El Chaar E, Almogahwi M, Abdalkader K, et al. Decontamination of the Infected Implant Surface: A Scanning Electron Microscope Study. Int J Periodontics Restorative Dent 2020;40:395-401. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lin GH, Suárez López Del Amo F, Wang HL. Laser therapy for treatment of peri-implant mucositis and peri-implantitis: An American Academy of Periodontology best evidence review. J Periodontol 2018;89:766-82. [PubMed]

- Chambrone L, Wang HL, Romanos GE. Antimicrobial photodynamic therapy for the treatment of periodontitis and peri-implantitis: An American Academy of Periodontology best evidence review. J Periodontol 2018;89:783-803. [PubMed]

- Shibli JA, Ferrari DS, Siroma RS, et al. Microbiological and clinical effects of adjunctive systemic metronidazole and amoxicillin in the non-surgical treatment of peri-implantitis: 1 year follow-up. Braz Oral Res 2019;33:e080. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Wang CW, Renvert S, Wang HL. Nonsurgical Treatment of Periimplantitis. Implant Dent 2019;28:155-60. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Roccuzzo A, Stähli A, Monje A, et al. Peri-Implantitis: A Clinical Update on Prevalence and Surgical Treatment Outcomes. J Clin Med 2021;10:1107. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Khoury F, Keeve PL, Ramanauskaite A, et al. Surgical treatment of peri-implantitis - Consensus report of working group 4. Int Dent J 2019;69:18-22. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Chan HL, Lin GH, Suarez F, et al. Surgical management of peri-implantitis: a systematic review and meta-analysis of treatment outcomes. J Periodontol 2014;85:1027-41. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Surveillance report 2018 – Dental checks: intervals between oral health reviews (2004) NICE guideline CG19. London: National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (UK), 2018. Available online: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK551810/

陶星如

就读于上海交通大学医学院。2019-2021年参与LncRNA相关课题,2021年11月协助发表综述《长链非编码RNA DUXAP9对头颈鳞癌细胞增殖和转移的影响》(《口腔疾病防治》);2021-2023年参加第十五期“大学生创新训练计划”《唇腭裂婴儿上颌牙槽骨口内扫描数字模型与石膏模型测量的对比研究》,项目2022年4月获评上海市级大学生创新创业训练计划项目。多次参加科普活动,2021年在上海交通大学医学院主办的“健康科普,摇篮计划”活动中视频作品获三等奖;2022年主创H5网页、折页《我的牙齿,发生肾么事了?》;2023年参加上海交通大学医学院举办的“为爱呐‘罕’,守护新生”活动,主创作品获评“优秀奖”。(更新时间:2023-07-02)

于德栋

上海交通大学医学院附属第九人民医院,医学博士,副主任医师,硕士生导师,荷兰ACTA种植修复科博士后。中华口腔医学会种植专业委员会青年委员;白求恩精神研究会口腔种植学组委员;上海口腔种植专业委员会委员;上海口腔遗传病与罕见病专业委员会委员;国际口腔种植协会专家委员会委员(ITI Fellow);国家自然科学基金通讯评审专家。(更新时间:2023-07-02)

(本译文仅供学术交流,实际内容请以英文原文为准。)

Cite this article as: Kwon T, Yen HH, Levin L. Peri-implant disease: early diagnosis and non-surgical treatment—a narrative literature review. Front Oral Maxillofac Med 2022;4:38.